In the software business there is an ongoing struggle between the pointy-headed academics, and another equally formidable force, the pointy-haired bosses. I believe everyone knows who the pointy-haired boss is.1 I think most people in the technology world not only recognize this cartoon character, but know the actual person in their company that he is modelled upon.

The pointy-haired boss miraculously combines two qualities that are common by themselves, but rarely seen together: (a) he knows nothing whatsoever about technology, and (b) he has very strong opinions about it.

Suppose, for example, you need to write a piece of software. The pointy-haired boss has no idea how this software has to work and can't tell one programming language from another, and yet he knows what language you should write it in. Exactly. He thinks you should write it in Java.

Why does he think this? Let's take a look inside the brain of the pointy-haired boss. What he's thinking is something like this. Java is a standard. I know it must be, because I read about it in the press all the time. Since it is a standard, I won't get in trouble for using it. And that also means there will always be lots of Java programmers, so if those working for me now quit, as programmers working for me mysteriously always do, I can easily replace them.

Well, this doesn't sound that unreasonable. But it's all based on one unspoken assumption, and that assumption turns out to be false. The pointy-haired boss believes that all programming languages are pretty much equivalent. If that were true, he would be right on target. If languages are all equivalent, sure, use whatever language everyone else is using.

But all languages are not equivalent, and I think I can prove this to you without even getting into the differences between them. If you asked the pointy-haired boss in 1992 what language software should be written in, he would have answered with as little hesitation as he does today. Software should be written in C++. But if languages are all equivalent, why should the pointy-haired boss's opinion ever change? In fact, why should the developers of Java have even bothered to create a new language?

Presumably, if you create anew language, it's because you think it's better in some way than what people already had. And in fact, Gosling makes it clear in the first Java white paper that Java was designed to fix some problems with C++. So there you have it: languages are not all equivalent. If you follow the trail through the pointy-haired boss's brain to Java and then back through Java's history to its origins, you end up holding an idea that contradicts the assumption you started with.

So, who's right? James Gosling, or the pointy-haired boss? Not surprisingly, Gosling is right. Some languages are better, for certain problems, than others. And you know, that raises some interesting questions. Java was designed to be better, for certain problems, than C++. What problems? When is Java better and when is C++? Are there situations where other languages are better than either of them?

Once you start considering this question, you've opened a real can of worms. If the pointy-haired boss had to think about the problem in its full complexity, it would make his head explode. As long as he considers all languages equivalent, all he has to do is choose the one that seems to have the most momentum, and since that's more a question of fashion than technology, even he can probably get the right answer. But if languages vary, he suddenly has to solve two simultaneous equations, trying to find an optimal balance between two things he knows nothing about: the relative suitability of the twenty or so leading languages for the problem he needs to solve, and the odds of finding programmers, libraries, etc. for each. If that's what's on the other side of the door, it is no surprise that the pointy-haired boss doesn't want to open it.

The disadvantage of believing that all programming languages are equivalent is that it's not true. But the advantage is that it makes your life a lot simpler. And I think that's the main reason the idea is so widespread. It is a comfortable idea.

We know that Java must be pretty good, because it is the cool, new programming language. Or is it? If you look at the world of programming languages from a distance, it looks like Java is the latest thing. (From far enough away, all you can see is the large, flashing billboard paid for by Sun.) But if you look at this world up close, you find there are degrees of coolness. Within the hacker subculture, there is another language called Perl that is considered a lot cooler than Java. Slashdot, for example, is generated by Perl. I don't think you would find those guys using Java Server Pages. But there is another, newer language, called Python, whose users tend to look down on Perl, and another called Ruby that some see as the heir apparent of Python.

If you look at these languages in order, Java, Perl, Python, Ruby, you notice an interesting pattern. At least, you notice this pattern if you are a Lisp hacker. Each one is progressively more like Lisp. Python copies even features that many Lisp hackers consider to be mistakes. And if you'd shown people Ruby in 1975 and described it as a dialect of Lisp with syntax, no one would have argued with you. Programming languages have almost caught up with 1958.

What I mean is that Lisp was first discovered by John McCarthy in 1958, and popular programming languages are only now catching up with the ideas he developed then.

Now, how could that be true? Isn't computer technology something that changes very rapidly? In1958, computers were refrigerator-sized behemoths with the processing power of a wristwatch.2 How could any technology that old even be relevant, let alone superior to the latest developments?

Figure 13-1. IBM 704, Lawrence Livermore, 1956.

I'll tell you how. It's because Lisp was not really designed to be a programming language, at least not in the sense we mean today. What we mean by a programming language is something we use to tell a computer what to do. McCarthy did eventually intend to develop a programming language in this sense, but the Lisp we actually ended up with was based on something separate that he did as a theoretical exercise—an effort to define a more convenient alternative to the Turing machine. As McCarthy said later,

Another way to show that Lisp was neater than Turing machines was to write a universal Lisp function and show that it is briefer and more comprehensible than the description of a universal Turing machine. This was the Lisp function eval..., which computes the value of a Lisp expression....Writing eval required inventing a notation representing Lisp functions as Lisp data, and such a notation was devised for the purposes of the paper with no thought that it would be used to express Lisp programs in practice.

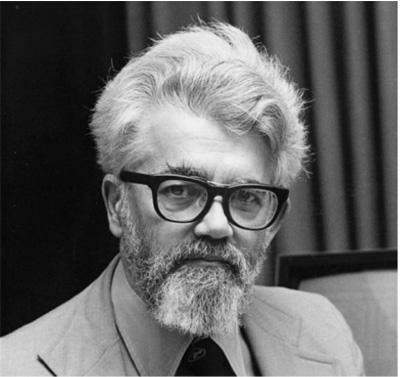

Figure 13-2. Alpha nerd: John McCarthy.

But in late1958, Steve Russell,3 one of McCarthy's grad students, looked at this definition of eval and realized that if he translated it into machine language, the result would be a Lisp interpreter.

This was a big surprise at the time. Here is what McCarthy said about it later:

Steve Russell said, look, why don't I program this eval..., and I said to him, ho, ho, you're confusing theory with practice, this eval is intended for reading, not for computing. But he went ahead and did it. That is, he compiled the eval in my paper into[IBM] 704machine code, fixing bugs, and then advertised this as a Lisp interpreter, which it certainly was. So at that point Lisp had essentially the form that it has today....

Suddenly, in a matter of weeks, McCarthy found his theoretical exercise transformed into an actual programming language—and a more powerful one than he had intended.

So the short explanation of why this 1950s language is not obsolete is that it was not technology but math, and math doesn't get stale. The right thing to compare Lisp to is not 1950s hardware but the Quick sort algorithm, which was discovered in 1960 and is still the fastest general-purpose sort.

There is one other language still surviving from the 1950s, Fortran, and it represents the opposite approach to language design. Lisp was a piece of theory that unexpectedly got turned into a programming language. Fortran was developed intentionally as a programming language, but what we would now consider a very low-level one.

Fortran I, the language that was developed in 1956, was a very different animal from present-day Fortran. Fortran I was pretty much assembly language with math. In some ways it was less powerful than more recent assembly languages; there were no subroutines, for example, only branches. Present-day Fortran is now arguably closer to Lisp than to Fortran I.

Lisp and Fortran were the trunks of two separate evolutionary trees, one rooted in math and one rooted in machine architecture. These two trees have been converging ever since. Lisp started out powerful, and over the next twenty years got fast. So-called mainstream languages started out fast, and over the next forty years gradually got more powerful, until now the most advanced of them are fairly close to Lisp. Close, but they are still missing a few things.

When it was first developed, Lisp embodied nine new ideas. Some of these we now take for granted, others are only seen in more advanced languages, and two are still unique to Lisp. The nine ideas are, in order of their adoption by the mainstream,

Conditionals. A conditional is an if-then-else construct. We take these for granted now, but Fortran I didn't have them. It had only a conditional go to closely based on the underlying machine instruction.

A function type. In Lisp, functions are a data type just like integers or strings. They have a literal representation, can be stored in variables, can be passed as arguments, and so on.

Recursion. Lisp was the first high-level language to support recursive functions.4

Dynamic typing. In Lisp, all variables are effectively pointers. Values are what have types, not variables, and assigning values to variables means copying pointers, not what they point to.

Garbage-collection.

Programs composed of expressions. Lisp programs are trees of expressions, each of which returns a value. This is in contrast to Fortran and most succeeding languages, which distinguish between expressions and statements.

This distinction was natural in Fortran I because you could not nest statements. So while you needed expressions for math to work, there was no point in making anything else return a value, because there could not be anything waiting for it.

This limitation went away with the arrival of block-structured languages, but by then it was too late. The distinction between expressions and statements was entrenched. It spread from Fortran into Algol and then to both their descendants.

A symbol type. Symbols are effectively pointers to strings stored in a hash table. So you can test equality by comparing a pointer, instead of comparing each character.

A notation for code using trees of symbols and constants.

The whole language there all the time. There is no real distinction between read-time, compile-time, and runtime. You can compile or run code while reading, read or run code while compiling, and read or compile code at runtime.

Running code at read-time lets users reprogram Lisp's syntax; running code at compile-time is the basis of macros; compiling at runtime is the basis of Lisp's use as an extension language in programs like Emacs; and reading at runtime enables programs to communicate using s-expressions, an idea recently reinvented as XML.5

When Lisp first appeared, these ideas were far removed from ordinary programming practice, which was dictated largely by the hardware available in the late 1950s. Over time, the default language, embodied in a succession of popular languages, has gradually evolved toward Lisp. Ideas 1-5 are now widespread. Number 6 is starting to appear in the mainstream. Python has a form of 7, though there doesn't seem to be any syntax for it.

As for number 8, this may be the most interesting of the lot. Ideas 8and 9 only became part of Lisp by accident, because Steve Russell implemented something McCarthy had never intended to be implemented. And yet these ideas turn out to be responsible for both Lisp's strange appearance and its most distinctive features. Lisp looks strange not so much because it has a strange syntax as because it has no syntax; you express programs directly in the parse trees that get built behind the scenes when other languages are parsed, and these trees are made of lists, which are Lisp data structures.

Expressing the language in its own data structures turns out to be a very powerful feature. Ideas 8 and 9 together mean that you can write programs that write programs. That may sound like a bizarre idea, but it's an everyday thing in Lisp. The most common way to do it is with something called a macro.

The term "macro" does not mean in Lisp what it means in other languages. A Lisp macro can be anything from an abbreviation to a compiler for a new language. If you really want to understand Lisp, or just expand your programming horizons, I would learn more about macros.

Macros (in the Lisp sense) are still, as far as I know, unique to Lisp. This is partly because in order to have macros you probably have to make your language look as strange as Lisp. It may also be because if you do add that final increment of power, you can no longer claim to have invented a new language, but only a new dialect of Lisp.

I mention this mostly as a joke, but it is quite true. If you define a language that has car, cdr, cons, quote, cond, atom, eq, and a notation for functions expressed as lists, then you can build all the rest of Lisp out of it. That is in fact the defining quality of Lisp: it was in order to make this so that McCarthy gave Lisp the shape it has.

Even if Lisp does represent a kind of limit that mainstream languages are approaching asymptotically, does that mean you should actually use it to write software? How much do you lose by using a less powerful language? Isn't it wiser, sometimes, not to be at the very edge of innovation? And isn't popularity to some extent its own justification? Isn't the pointy-haired boss right, for example, to want to use a language for which he can easily hire programmers?

There are, of course, projects where the choice of programming language doesn't matter much. As a rule, the more demanding the application, the more leverage you get from using a powerful language. But plenty of projects are not demanding at all. Most programming probably consists of writing little glue programs, and for little glue programs you can use any language that you're already familiar with and that has good libraries for whatever you need to do. If you just need to feed data from one Windows app to another, sure, use Visual Basic.

You can write little glue programs in Lisp too (I use it as a desktop calculator), but the biggest win for languages like Lisp is at the other end of the spectrum, where you need to write sophisticated programs to solve hard problems in the face of fierce competition. A good example is the airline fare search program that ITA Software licenses to Orbitz. These guys entered a market already dominated by two big, entrenched competitors, Travelocity and Expedia, and seem to have just humiliated them technologically.

The core of ITA's application is a 200,000-line Common Lisp program that searches many orders of magnitude more possibilities than their competitors, who apparently are still using mainframe-era programming techniques. I have never seen any of ITA's code, but according to one of their top hackers they use a lot of macros, and I am not surprised to hear it.

I'm not saying there is no cost to using uncommon technologies. The pointy-haired boss is not completely mistaken to worry about this. But because he doesn't understand the risks, he tends to magnify them.

I can think of three problems that could arise from using less common languages. Your programs might not work well with programs written in other languages. You might have fewer libraries at your disposal. And you might have trouble hiring programmers.

How big a problem is each of these? The importance of the first varies depending on whether you have control over the whole system. If you're writing software that has to run on a remote user's machine on top of a buggy, proprietary operating system (I mention no names), there may be advantages to writing your application in the same language as the OS. But if you control the whole system and have the source code of all the parts, as ITA presumably does, you can use whatever languages you want. If any incompatibility arises, you can fix it yourself.

In server-based applications you can get away with using the most advanced technologies, and I think this is the main cause of what Jonathan Erickson calls the "programming language renaissance." This is why we even hear about new languages like Perl and Python. We're not hearing about these languages because people are using them to write Windows apps, but because people are using them on servers. And as software shifts off the desktop and onto servers (a future even Microsoft seems resigned to), there will be less and less pressure to use middle-of-the-road technologies.

As for libraries, their importance also depends on the application. For less demanding problems, the availability of libraries can outweigh the intrinsic power of the language. Where is the breakeven point? Hard to say exactly, but wherever it is, it is short of anything you'd be likely to call an application. If a company considers it self to be in the software business, and they're writing an application that will be one of their products, then it will probably involve several hackers and take at least six months to write. In a project of that size, powerful languages probably start to outweigh the convenience of pre-existing libraries.

The third worry of the pointy-haired boss, the difficulty of hiring programmers, I think is a red herring. How many hackers do you need to hire, after all? Surely by now we all know that software is best developed by teams of less than ten people. And you shouldn't have trouble hiring hackers on that scale for any language anyone has ever heard of. If you can't find ten Lisp hackers, then your company is probably based in the wrong city for developing software.

In fact, choosing a more powerful language probably decreases the size of the team you need, because (a) if you use a more powerful language, you probably won't need as many hackers, and (b) hackers who work in more advanced languages are likely to be smarter.

I'm not saying that you won't get a lot of pressure to use what are perceived as "standard" technologies. At Via web we raised some eyebrows among VCs and potential acquirers by using Lisp. But we also raised eyebrows by using generic Intel boxes as servers instead of "industrial strength" servers like Suns, for using a then-obscure open source Unix called FreeBSD instead of a real commercial OS like Windows NT, for ignoring a supposed e-commerce standard called SET that no one now even remembers, and so on.

You can't let the suits make technical decisions for you. Did it alarm potential acquirers that we used Lisp? Some, slightly, but if we hadn't used Lisp, we wouldn't have been able to write the software that made them want to buy us. What seemed like an anomaly to them was in fact cause and effect.

If you start a startup, don't design your product to please VCs or potential acquirers. Design your product to please the users. If you win the users, everything else will follow. And if you don't, no one will care how comfortingly orthodox your technology choices were.

How much do you lose by using a less powerful language? There is actually some data out there about that.

The most convenient measure of power is probably code size. The point of high-level languages is to give you bigger abstractions—bigger bricks, as it were, so you don't need as many to build a wall of a given size. So the more powerful the language, the shorter the program (not simply in characters, of course, but in distinct elements).

How does a more powerful language enable you to write shorter programs? One technique you can use, if the language will let you, is something called bottom-up programming. Instead of simply writing your application in the base language, you build on top of the base language a language for writing programs like yours, then write your program in it. The combined code can be much shorter than if you had written your whole program in the base language—indeed, this is how most compression algorithms work. A bottom-up program should be easier to modify as well, because in many cases the language layer won't have to change at all.

Code size is important, because the time it takes to write a program depends mostly on its length. If your program would be three times as long in another language, it will take three times as long to write—and you can't get around this by hiring more people, because beyond a certain size new hires are actually a net lose. Fred Brooks described this phenomenon in his famous book The Mythical Man-Month, and everything I've seen has tended to confirm what he said.

So how much shorter are your programs if you write them in Lisp? Most of the numbers I've heard for Lisp versus C, for example, have been around 7-10x. But a recent article about ITA in New Architect magazine said that "one line of Lisp can replace 20 lines of C," and since this article was full of quotes from ITA's president, I assume they got this number from ITA.6 If so then we can put some faith in it; ITA's software includes a lot of C and C++ as well as Lisp, so they are speaking from experience.

My guess is that these multiples aren't even constant. I think they increase when you face harder problems and also when you have smarter programmers. A really good hacker can squeeze more out of better tools.

As one data point on the curve, at any rate, if you were to compete with ITA and chose to write your software in C, they would be able to develop software twenty times faster than you. If you spent a year on a new feature, they'd be able to duplicate it in less than three weeks. Whereas if they spent just three months developing something new, it would be five years before you had it too.

And you know what? That's the best-case scenario. When you talk about code-size ratios, you're implicitly assuming that you can actually write the program in the weaker language. But in fact there are limits on what programmers can do. If you're trying to solve a hard problem with a language that's too low-level, you reach a point where there is just too much to keep in your head at once.

So when I say it would take ITA's imaginary competitor five years to duplicate something ITA could write in Lisp in three months, I mean five years if nothing goes wrong. In fact, the way things work in most companies, any development project that would take five years is likely never to get finished at all.

I admit this is an extreme case. ITA's hackers seem to be unusually smart, and C is a pretty low-level language. But in a competitive market, even a differential of two or three to one would be enough to guarantee that you'd always be behind.

This is the kind of possibility that the pointy-haired boss doesn't even want to think about. And so most of them don't. Because, you know, when it comes down to it, the pointy-haired boss doesn't mind if his company gets their ass kicked, so long as no one can prove it's his fault. The safest plan for him personally is to stick close to the center of the herd.

Within large organizations, the phrase used to describe this approach is "industry best practice." Its purpose is to shield the pointy-haired boss from responsibility: if he chooses something that is "industry best practice," and the company loses, he can't be blamed. He didn't choose, the industry did.

I believe this term was originally used to describe accounting methods and so on. What it means, roughly, is don't do anything weird. And in accounting that's probably a good idea. The terms "cutting-edge" and "accounting" do not sound good together. But when you import this criterion into decisions about technology, you start to get the wrong answers.

Technology often should be cutting-edge. In programming languages, as Erann Gat has pointed out, what "industry best practice" actually gets you is not the best, but merely the average. When a decision causes you to develop software at a fraction of the rate of more aggressive competitors, "best practice" does not really seem the right name for it.

So here we have two pieces of information that I think are very valuable. In fact, I know it from my own experience. Number 1, languages vary in power. Number 2, most managers deliberately ignore this. Between them, these two facts are literally a recipe for making money. ITA is an example of this recipe in action. If you want to win in a software business, just take on the hardest problem you can find, use the most powerful language you can get, and wait for your competitors' pointy-haired bosses to revert to the mean.

As an illustration of what I mean about the relative power of programming languages, consider the following problem. We want to write a function that generates accumulators—a function that takes a number n,and returns a function that takes another number i and returns n incremented by i. (That's incremented by, not plus. An accumulator has to accumulate.)

In Common Lisp7 this would be:

1 2(defun foo (n) (lambda (i) (incf n i)))

In Ruby it's almost identical:

1 2def foo (n) lambda {|i| n += i } end

Whereas in Perl 5 it's

1 2 3 4sub foo { my ($n) = @_; sub {$n += shift} }

which has more elements than the Lisp/Ruby version because you have to extract parameters manually in Perl.

In Smalltalk the code is also slightly longer than in Lisp and Ruby:

1 2 3 4foo: n |s| s := n. ^[:i| s := s+i. ]

because although in general lexical variables work, you can't do an assignment to a parameter, so you have to create a new variable s to hold the accumulated value.

In Javascript the example is, again, slightly longer, because Javascript retains the distinction between statements and expressions, so you need explicit return statements to return values:

1 2 3function foo (n) { return function (i) { return n += i } }

(To be fair, Perl also retains this distinction, but deals with it in typical Perl fashion by letting you omit returns.)

If you try to translate the Lisp/Ruby/Perl/Smalltalk/Javascript code into Python you run into some limitations. Because Python doesn't fully support lexical variables, you have to create a data structure to hold the value of n. And although Python does have a function data type, there is no literal representation for one (unless the body is only a single expression) so you need to create a named function to return. This is what you end up with:

1 2 3 4 5 6def foo (n): s = [n] def bar (i): s[0] += i return s[0] return bar

Python users might legitimately ask why they can't just write

1 2 3 4 5def foo (n): return lambda i: return n += i or even def foo (n): lambda i: n += i

and my guess is that they probably will, one day. (But if they don't want to wait for Python to evolve the rest of the way into Lisp, they could always just...)

In OO languages, you can, to a limited extent, simulate a closure (a function that refers to variables defined in surrounding code) by defining a class with one method and a field to replace each variable from an enclosing scope. This makes the programmer do the kind of code analysis that would be done by the compiler in a language with full support for lexical scope, andit won't work if more than one function refers to the same variable, but it is enough in simple cases like this.

Python experts seem to agree that this is the preferred way to solve the problem in Python, writing either

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15def foo (n): class acc: def _ _init_ _ (self, s): self.s = s def inc (self, i): self.s += i return self.s return acc (n).inc or class foo: def _ _init_ _ (self, n): self.n = n def _ _call_ _ (self, i): self.n += i return self.n

I include these because I wouldn't want Python advocates to say I was misrepresenting the language, but both seem to me more complex than the first version. You're doing the same thing, setting up a separate place to hold the accumulator; it's just a field in an object instead of the head of a list. And the use of these special, reserved field names, especially _ _call_ _, seems a bit of a hack.

In the rivalry between Perl and Python, the claim of the Python hackers seems to be that Python is a more elegant alternative to Perl, but what this case shows is that power is the ultimate elegance: the Perl program is simpler (has fewer elements), even if the syntax is a bit uglier.

How about other languages? In the other languages mentioned here—Fortran, C, C++, Java, and Visual Basic—it does not appear that you can solve this problem at all. Ken Anderson says this is about as close as you can get in Java:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12public interface Inttoint { public int call (int i); } public static Inttoint foo (final int n) { return new Inttoint () { int s = n; public int call (int i) { s = s + i; return s; }}; }

which falls short of the spec because it only works for integers.

It's not literally true that you can't solve this problem in other languages, of course. The fact that all these languages are Turing-equivalent means that, strictly speaking, you can write any program in any of them. So how would you do it? In the limit case, by writinga Lisp interpreter in the less powerful language.

That sounds like a joke, but it happens so often to varying degrees in large programming projects that there is a name for the phenomenon, Greenspun's Tenth Rule:

Any sufficiently complicated C or Fortran program contains an ad hoc informally-specified bug-ridden slow implementation of half of Common Lisp.

If you try to solve a hard problem, the question is not whether you will use a powerful enough language, but whether you will (a) use a powerful language, (b) write a de facto interpreter for one, or (c) yourself become a human compiler for one. We see this already beginning to happen in the Python example, where we are in effect simulating the code that a compiler would generate to implement a lexical variable.

This practice is not only common, but institutionalized. For example, in the OO world you hear a good deal about "patterns." I wonder if these patterns are not sometimes evidence of case (c), the human compiler, at work.8 When I see patterns in my programs, I consider it a sign of trouble. The shape of a program should reflect only the problem it needs to solve. Any other regularity in the code is a sign, to me at least, that I'm using abstractions that aren't powerful enough—often that I'm generating by hand the expansions of some macro that I need to write.

Copyright ©2010-2022 比特日记 All Rights Reserved.